An Exegesis Concerning an Essay with My Friend Stefano.

Something curious happens when you say “call me by my name” to students. There is no professor here. There are no professors at all. I’m no better than you; just have a few more days on this planet. Something occurs when students cease to feel like students and start to act as real future architects, exploring, experimenting, inventing, being themselves searching for something (nobody knows what). There is something very fruitful about saying there is no such thing as a genius and there’s nothing as grading the geniality of a project. That’s absurd. Do your work with care —the same care you devote to what you really love. This care will remain in the project and the future building, and that’s why someone, someday, could have a meaningful experience of it. There are no guarantees in architecture, so don’t be preoccupied by them.

The most interested person here in what you’re doing is me. I am more interest in what you’re doing and how you’re doing than you might be. Yes, that’s true. You still don’t have clarity about what you’re really doing. In the beginning, you’re just learning. But it’s not as simple as that: you’re doing and then learning. You’re learning through doing. I’m interested in your doing. Learning is your topic —sorry, not mine. However, if you’re honest and open to the idea of not knowing everything in advance, you’ll discover something. I’ll be just a slight push.

There’s no final image, goal, objective, product, that students should pursue. That’s a huge mistake in teaching architecture, or any other art. There are only particular ways of doing things. What future serious (i.e., playful) architects need is to found their own particular way —to found themselves, their hands, their traces, their eyes and ways of seeing. Since there’s no set “imagery”, you’ll have to trust the process.

Professors need to be like meditation masters. They don’t teach you how to meditate; they’re there just to filter out bad energy for you, to create a positive environment. How do they do that? Through decades of persistence practice. Resistance. Effort. Not a goal. Imagine the difficulty of being just a filter. Professors, at least in the arts, should sustain, perhaps even physically, the studio, ensuring that no student falls behind during the semester, that everyone keeps going, that no one lets go of the rope. Teach them the beauty of courage, the value of risk, and the truth of will.

Show your hard work, your effort alongside them, your genuine interest in the studio, and students will notice. Trust them. Show them your scars —there’s no shame on doing so. Protect them. Be honest and transparent, and students will trust you, and embrace the journey with you.

A couch on a team: professors don’t make the goals. They don’t take the final shot from the 3-point line with 2 seconds left. They’ll never do a “hand of god”. There’s undoubtedly some melancholy in that —the unacceptable tragedy of become a professor. You need to do it well, to do it right, because there’s an unending line of others just like you —better or worse, but just like you. Yet, you’re aware of that. And that’s your consolation.

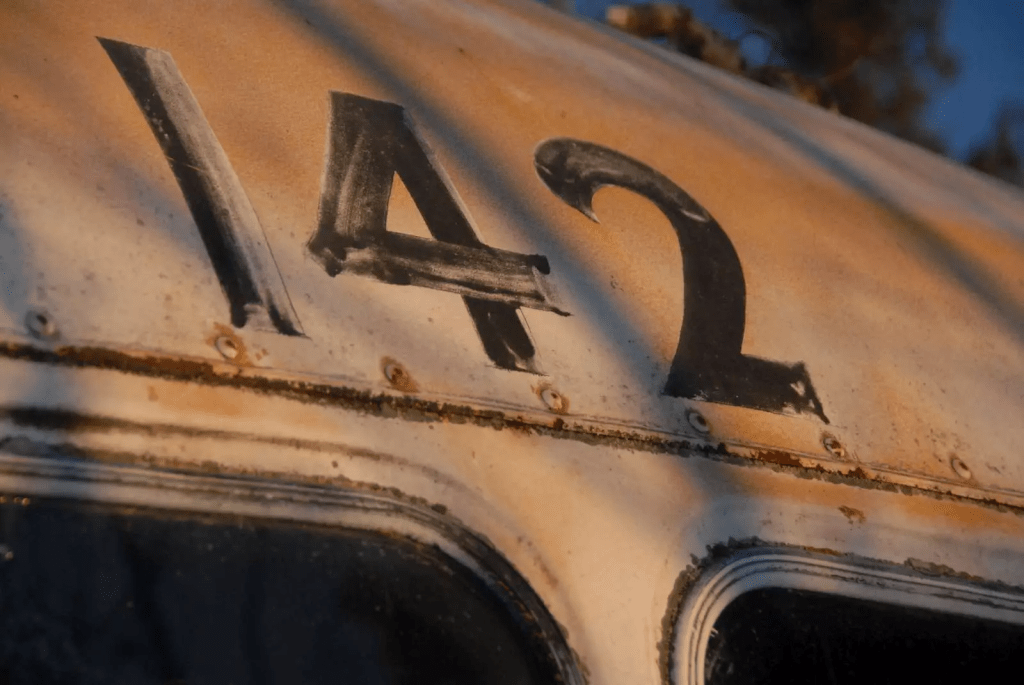

P.S. The accent is on the “i”, but without the mark.

Leave a comment